Molecular ConvNet in Property Prediction

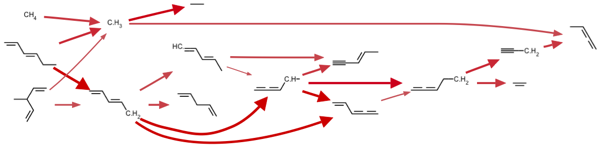

In chemistry discovery, we try to explore vast, unknown chemical space (molecules and reactions) and discover most essential chemistry for specific chemical systems. By doing that, we are able to purposefully create valuable applications such as optimizing fuel-additive ratio for engine combustion, new drug discovery for certain types of dieseas, etc. In order to automate the discovery process, we’ve developed an open source project RMG-Py, of which some useful tools are available in RMG-website.

In that process, one of the most challenging problems is to predict thermodynamic properties (e.g., enthalpy, entropy, heat capacities) for any molecules in the chemical space, of which most we may have never seen before.

In machine learning language, molecular prediction research is essentially answer how to smartly map a molecule, regarded as a node-edge graph, to a feature vector and then design appropriate regression model to get to molecular property.

This post reviews several traditional approaches (used as base-line models) and propose a new solution using Molecular Convolutional Neural Networks, which boosts prediction performance remarkably.

0. Datasets

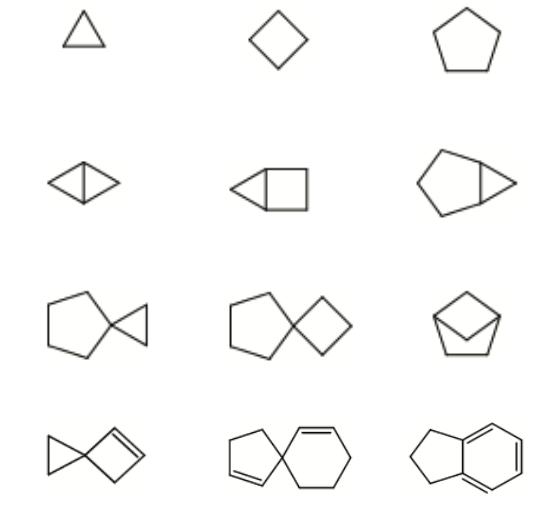

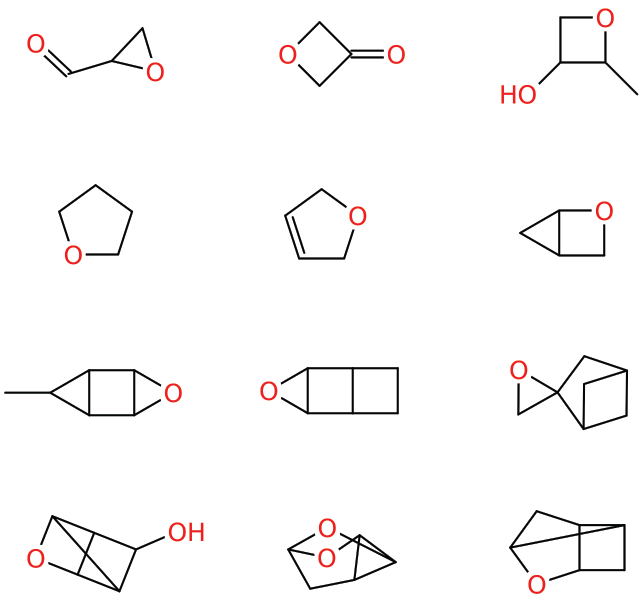

The datasets we are using are crafted originally from a large quantum-mechanics calculation dataset named ScientificData-134k (thereafter sdata134k) by Ramakrishnan. Since the most difficult-to-predict molecules always involves cyclic structures, this post gathers all cyclic molecules from sdata134k and categorizes them into into hydrocarbon cyclics and oxygen-contained cyclics.

Dataset 1: sdata134k-hydrocarbon-cyclic examples

Dataset 2: sdata134k-oxygenate-cyclic examples

1. Base-line models

The traditional approaches that will be covered and used as base-line models includes

-

Linear model: Group additivity method

-

Molecular fingerprint with neural netoworks

Base-line model 1: Group addtivity method

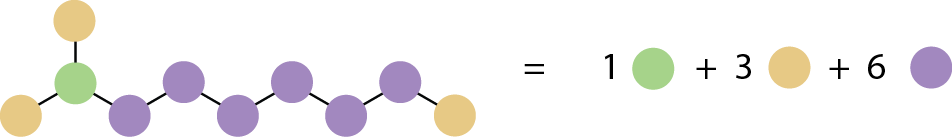

Historically, Benson Group Additivity Method is polularly used because of its simplicity. It breaks down a molecule into sub-structural pieces and sums up their contributions to overall thermodynamic properties, which essentially is a linear model with bag of sub-structures.

For example, the molecule 2-methylnonane consists of three types of sub-structures includes:

- 1 tertiary carbon atom

- 6 secondary carbon atoms

- 3 primary carbon atoms

This simple idea is effective for linear-shaped molecules, but for the cyclic molecules collected in the above two datasets, Benson Group Additivity approach (already implemented in RMG thermo estimator) performs badly:

- Enthalpy energy prediction

test error = 60 kcal/mol(RMSE).

The error largely comes from its underlying design/assumption:

- the effect of relative positions of sub-structures is negiligle (independent contributions from sub-structures)

- sub-structures are very small, usually atom based

The assumptions become less valid when it comes to cyclic compounds since they are relatively large molecules with strong interations between sub-structures.

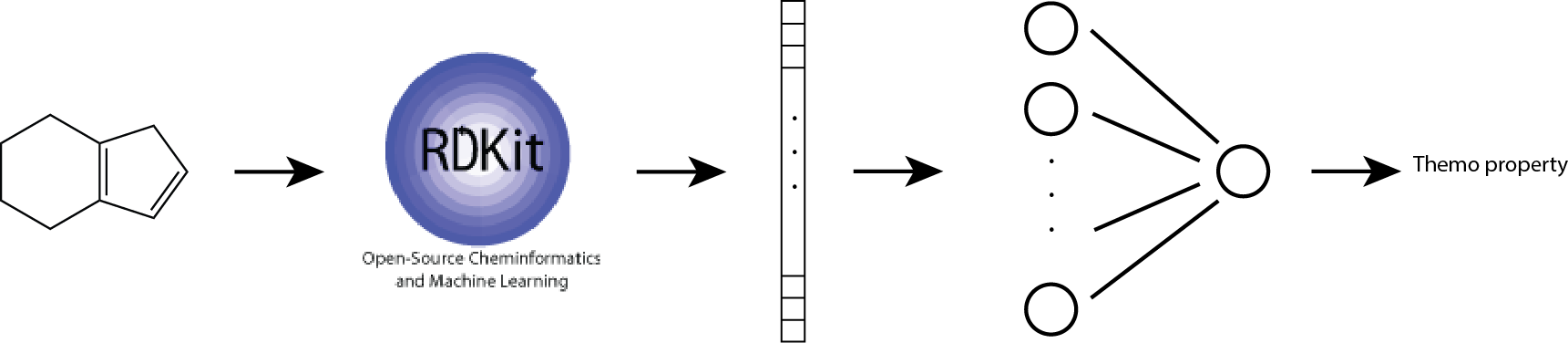

Base-line model 2: Morgan fingerprint with neural net

Morgan fingerprint, also known as ECFP (Extended-Connectivity Fingerprint) tries to see bigger chemical environments within a moleucle. It defines fragments with user-specified radius (e.g., 2-atom distance radius). More details can be found in RDKit presentation.

In this base-line model, we use Morgan fingerprint as our molecular feature vector. We also use one-hidden-layer neural networks to account for non-linear interations between fragments.

The architecture is shown below:

This approach of combining Morgan fingerprint and non-linear regression model improves prediction performance:

- Enthalpy energy prediction

test error = 19 kcal/mol(RMSE).

However, 19 kcal/mol is still not satisfying in chemistry discovery; to our experience, enthalpy energy uncertainty of larger than 5 kcal/mol could easily mis-guide discovery direction.

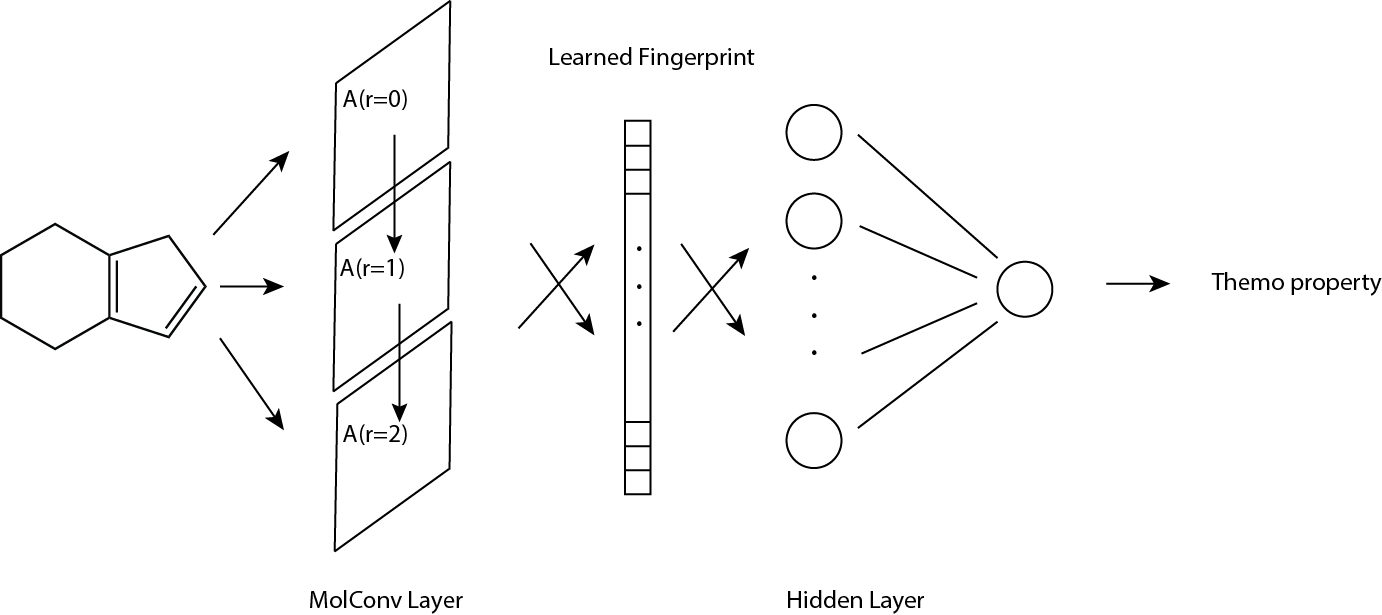

2. Molecular convolutional neural network

Besides accuracy issue, for fixed molecular fingerprint, people face the practical challenge that feature engineering requires chemical expertise and manual tweaking, naturally slowing down the process of learning from data.

To solve that, one idea by Aspuru-Guzik is to make fingerprint also learnable from data. Thus, this project is actually to build an accurate enthalpy estimator that learns featurization and regression altogether from data.

More specifically, the learnable featurization module uses graph convolutional neural networks (see architecture below). The learned feature vector willthen be fed into a fully connected neural network with one hidden layer, which serves the regression model.

Architecture

Each input molecule to molecular convolutional neural network (thereafter MCNN) is represented by three components: atom fingerprint matrix (denoted by A), bond fingerprint tensor (denoted by B), connectivity matrix (denoted by C).

For dimensionality, \(A\) is \(n_a × f_a\), \(B\) is \(n_a × n_a × f_b\), and \(C\) is \(n_a × n_a\), where \(n_a\) is the number of atoms, \(f_a\) the size of atom fingerprint and \(f_b\) the size of bond fingerprint. The output of MCNN is molecular fingerprint vector with size of \(f_m\).

Atom fingerprint matrix \(A\)

For a given molecule, \(A\) stores the information at atom level; each atom has a fingerprint vector therefore \(A\) has size of \(n_a × f_a\). Atom fingerprint includes basic atomic information such as atomic charge, number of attached hydrogens, etc.

Bond fingerprint matrix \(B\)

For a given molecule, \(B\) stores the information at bond level; each bond has a fingerprint vector therefore \(B\) has size of na × na × fb. Bond fingerprint includes basic information such as bond order, whether the bond is in ring, etc.

Connectivity matrix \(C\)

For a given molecule, each possible pair of atoms has an entry in \(C\); 1 indicates there’s a bond between the pair, vice versa, therefore \(C\) has size of \(n_a × n_a\).

Molecular convolution

We could add each atom fingerprint to its local neighbors by some weights if neccessary, called molecular convolution, using \(A\) and \(C\), and get convoluted atom fingerprint matrix \(A^{r=1}\). r = 1 indicates the output fingerprint contains local information with radius of 1 atom distance. Increasing radius by consecutive convolution gives \(A^{r=m}\) which captures larger local neighborhood information.

Performance

The best model selected from 5-fold cross-validation gives remarkable preformance boost:

- Enthalpy energy prediction

test error = 3 kcal/mol(RMSE).

Interpretation

Let’s see if the learned fingerprint makes sense.

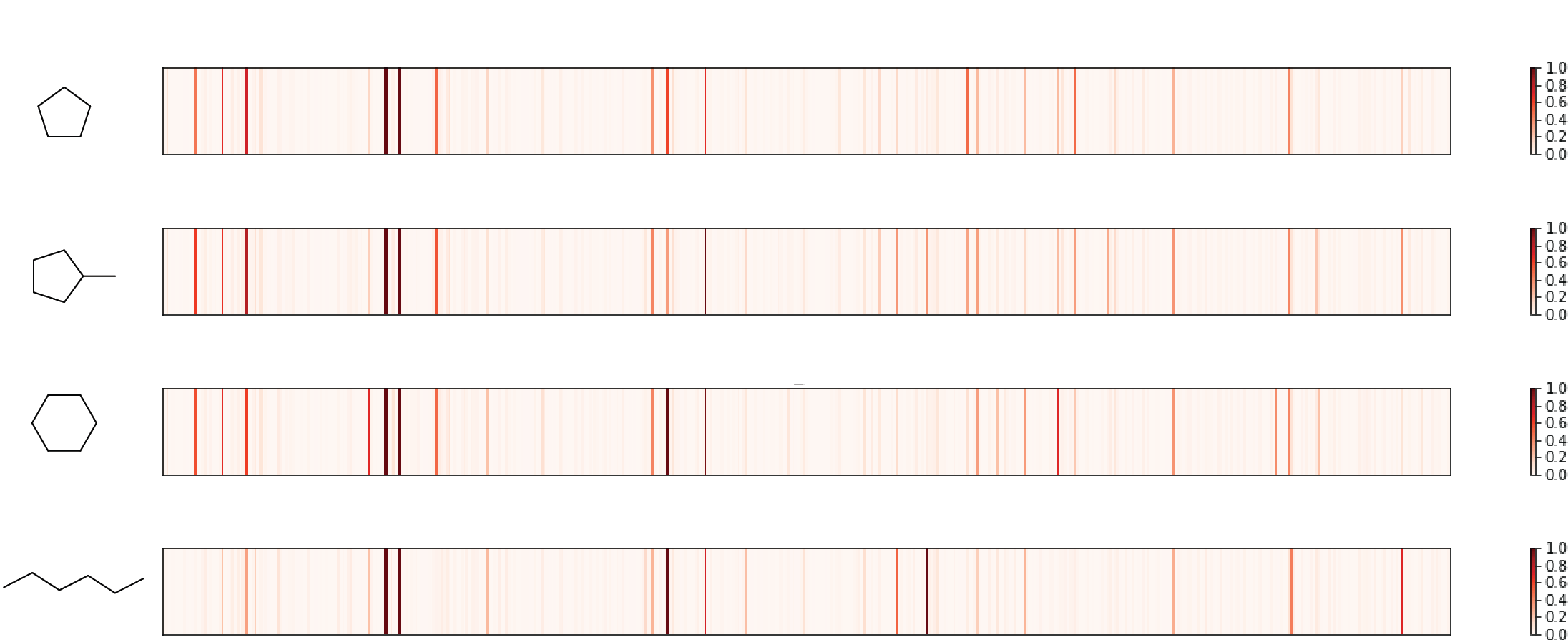

Check 1: similar molecules with similar fingerprint

Three similar cyclic hydrocarbon (first three in the figure) are selected, whose fingerprints share major high peaks. A linear molecule with same number of carbons appears relatively different, as expected. So, pass!

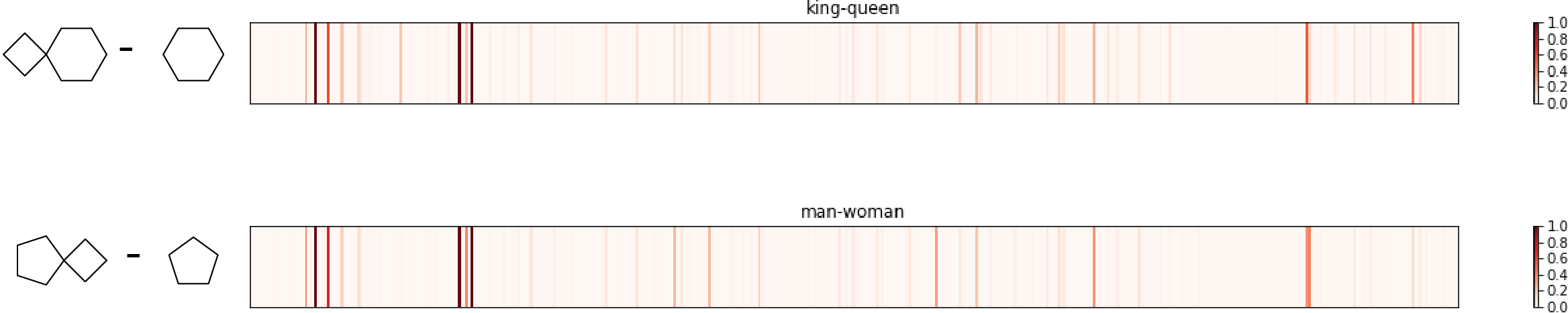

Check 2: king-queen =? man-woman

In word2vec project, researchers tends to use subtraction to interpret embedding vector (word equivalent of fingerprint). One of the most famous examples is using word2vec, vector(king)-vector(queen) is very similar to vector(man)-vector(woman), as semantics requires.

Similarly, four molecules are selected:

Again, the king molecule and queen molecule differ by a 4-member ring, same as for the difference between man molecule and woman molecule. The two fingerpring differences are quite similar, sharing most major high peaks. Another pass!

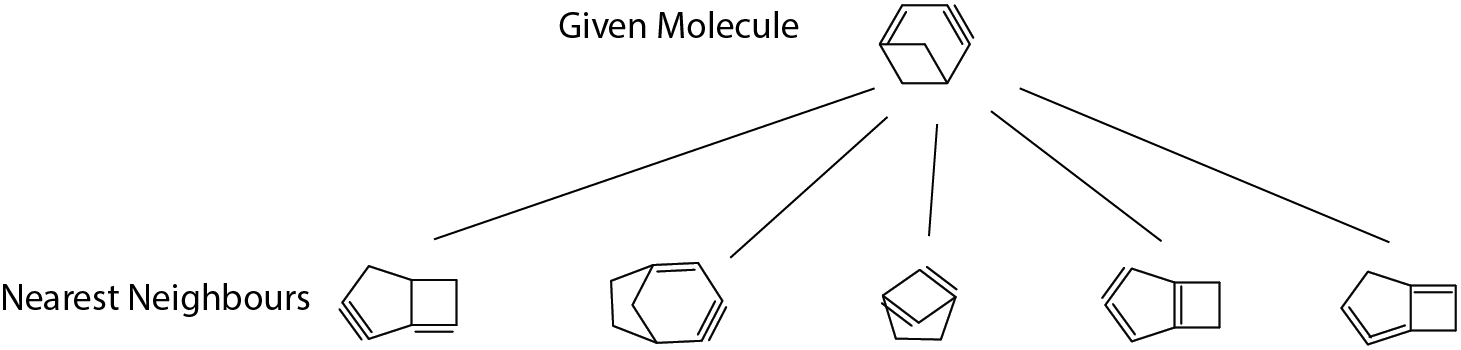

Check 3: nearest neighbor in fingerprint space

Although there’s no absolute definition of molecular similarity, human can generally tell if two molecular structures are alike. This check is to see if the machine generates sensible similar molecules in the training set given any molecules.

The given molecule example in the figure consists of a 4-member ring and 6-member ring; since 6-member and 5-member are quite similar (both have similar ring strain contributions), we see most returned neighbours have a 4-member ring and either one 5-member or one 6-member ring. Looking good!

Another aspect is unsaturated bonds in the given molecule: one double bond next to the fused bridge and one far-away triple bond. The second neighbour from left is exactly matching this aspect and all the remaining neighbours also have two similar unsaturated parts in structure. Pass!

At this point, we’ve kind of got a new model/estimator that appears to have greatly better accuracy and generate sensible fingerprints (although we still don’t exactly know what each entry in the fingerprint vector stands for).

3. Effectiveness of learning new data

Besides accuracy and interpretability, it’s also crucial to evaluate how effectively the new machine architecture learns from new data.

It is because the range of applications RMG explores keeps extending; along the past 10 years, RMG started from modeling nature gas combustion (usually small simple molecules) to recently being capable of handling full chemistry of hydrocarbon up to 20 carbons (obviously a lot new molecular structures come into our scope). On the other hand, it’s extending its capability towards oxygenates, sulfurides and nitrogen compounds as well.

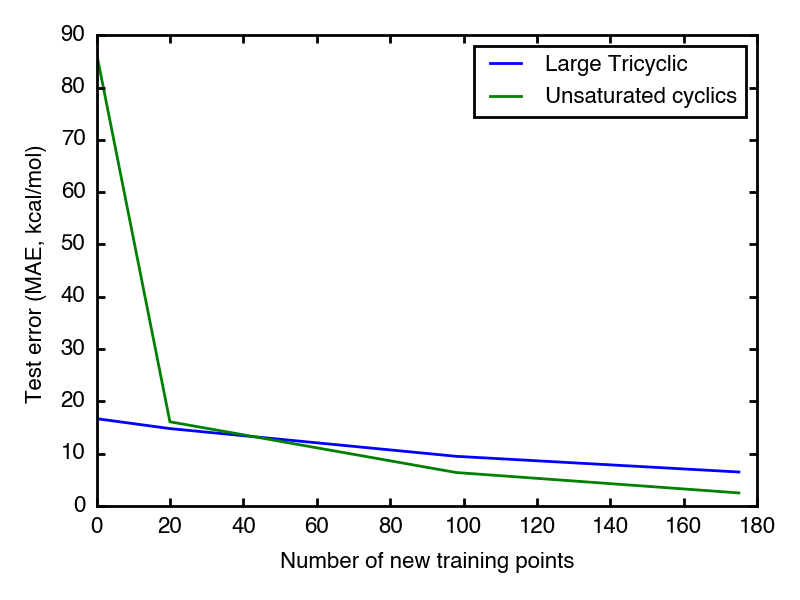

So, here we prepared two extra small datasets, whose molecules are distinct from those in the above training datasets.

-

Large tricyclic: larger rings that those in previous training datasets but mostly have saturated bonds as previous training examples do

-

Unsaturated cyclics: cyclics that have multiple unsaturated bonds in same ring, which is very distinct from preivous training examples.

As expected, the unsaturated cyclic dataset starts with higher test error than large tricyclic one, which is because its examples are much more different from previous training examples than the other.

Good news is both datasets have test error go down as feeding more new relavent data points. After 50 new data points, the test error enters 10 kcal/mol region.

4. Future work

The new proposed estimator appears much effective in predicting molecular themodynamic properties by mapping graph structures through fingerprints to eventually properties. To expand its predicting power to new categories of molecules, we’d make sure it can learn as long as new data is available. But data is a must to make this estimator evolve. To accomplish that, I’ll talk about data insfrastructure construction in next posts to build a data-machine pipeline.